Menu

The Fenian Raids in Canada West

Introduction

In 1866, John O’Neill led between 700 and 800 armed Irish-American republicans and supporters of the Fenian Brotherhood into Canada West. The invasion was part of a larger Fenian campaign to score military victories in British North America and use them as political leverage to liberate Ireland from British rule. Until the last Fenian raid in 1871, the Fenians failed to hold strategic locations, and their incursions were repelled. Ironically, the Fenians contributed to strengthening, rather than weakening, British North America. The Fenian threat heightened public support for the Canadian militia as the British Colonial Office sought to reduce its military commitments in the colonies. It also reinforced support for Canadian Confederation in 1867. In these and other ways, the Fenian raids were significant in Ontario’s military and political development. The Fenian raids also marked the last invasion of the province now called Ontario.

The Fenian Brotherhood

To understand the Fenian incursions into Canada West, it is important to outline the motives and aims of those behind the offensive – the Fenian Brotherhood. This organization was founded by Irish republicans (most of whom were Catholic) who were fighting for Ireland’s political independence. Inspired by the French and American revolutions, the Irish republicans attempted their own revolution in 1798 but were defeated. After the Irish Rebellion of 1798, Ireland’s parliament was disbanded and Irish representatives were amalgamated into the British political system. Revolutionaries continued their struggle for an independent Irish Republic, ultimately culminating in the Irish War of Independence between 1919 and 1921.

During the mid-1840s, the Irish Famine led to mass emigration between 1847 and 1852. Hundreds of thousands of Irish refugees travelled to British North America, and nearly one million to the United States. Although Irish immigrants arrived in the “New World,” many Irish Catholics continued to harbour their “Old World” aspirations for an independent Irish Republic. For this reason, Irish revolutionaries welcomed conflict between the United States and the United Kingdom because they believed it would weaken the United Kingdom’s ability to suppress a revolution in Ireland. For instance, during the Rebellion of 1837-38, some Irish republicans supported the Hunter Patriot lodges despite the organization’s Protestant and abolitionist affiliations.

As the Irish population in North America surged during the 1840s and 1850s, Irish revolutionaries became increasingly bold. Among them was Michael Thomas O’Connor who, in 1848, claimed that there would be an imminent and overwhelming attack on British North America. The declaration was imaginary but the Irish revolutionaries continued to scheme and devised an ill-fated plan to invade Ireland with the support of the Russian navy during the Crimean War. Intent on giving the Irish revolutionary movement more structure, Irish revolutionary leaders met in Dublin and formed the Irish Republican Brotherhood on March 17, 1858. The following year, John O’Mahony founded the American branch. O’Mahony took inspiration from the Celtic warrior-hunter bands of ancient Gaelic Ireland – called Fianna – and named the American branch “the Fenian Brotherhood.”

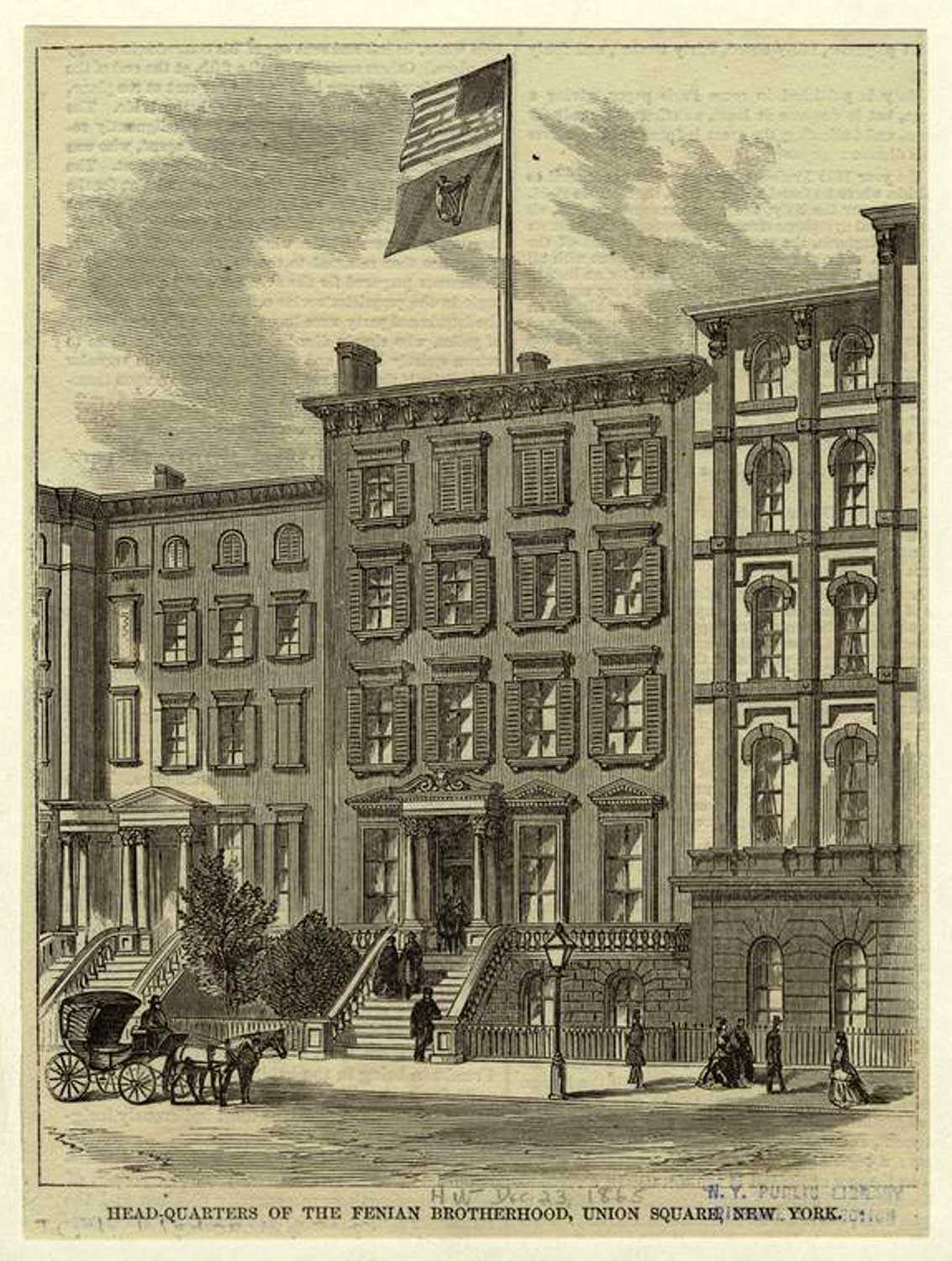

After the Fenian Brotherhood held its first Congress in Chicago in 1863, the organization thrived. Recruitment drives drew in thousands of volunteers, including many Irish-American Civil War veterans. Women’s auxiliaries were established to produce clothing, raise money and undertake other organizational duties. American politicians pandered to Fenian aspirations for votes. The Fenians even issued their own bonds, redeemable after achieving Irish independence, and used proceeds to fund their headquarters in the affluent area of Union Square, New York. Of course, the Fenian Brotherhood was a militaristic organization and gathered weapons and ammunition as well. A split occurred within the Brotherhood regarding the best strategy. O’Mahony believed that the military supplies and money should be sent directly to Ireland. In contrast, a rival faction led by William Roberts believed that military action against British North America would be an effective strategy to pressure the United Kingdom into conceding Irish independence.

Similar to the American generals during the War of 1812 and radical Reformers during the Rebellion of 1837-38, the Fenians overestimated the desire of Canada’s inhabitants to revolt against British rule. Even within Canada’s Irish-Catholic community, there was stern opposition to the Fenians’ strategy of military action against the colonies. Among the staunchest opponents was Thomas D’Arcy McGee. McGee was an elected representative for Montreal, and while a former activist in the Irish Republican movement, he became a strong advocate for peaceful reconciliation in Canada’s Irish-Catholic community. In addition to promoting peaceful reconciliation, McGee and other opponents of Fenian military action aided the British authorities by providing intelligence. In 1865, reports indicated that the Fenians were ready to attack.

The Fenian threat and the Canadian militia

The Fenian threat emerged during a pivotal period in the Province of Canada’s military development. During the 1850s, an increasing number of British policymakers wanted the Canadian government to oversee its own defence because in addition to the upkeep of the British garrison, British taxpayers were paying for several Canadian units to guard the Canada-United States border, including a Colored Corps of Black Canadians who guarded the Welland Canal. The necessity of these expenses was questionable. Relations between British North America and the United States improved significantly after the Canadian-American Reciprocity Treaty of 1854. The British government was also pressed by their military expenses elsewhere, especially their involvement in the Crimean War. And so, the British garrison was reduced during the 1850s, and Canada’s provincial units were disbanded.

In 1861, the American Civil War reignited fears of a war between the United States and the United Kingdom. In November, an American warship captured two Confederate envoys from the British steamship, the RMS Trent. In reaction to what became known as the Trent Affair, the British deployed over 10,000 troops to guard the colonies against further American aggression. It was during this time that British policymakers secretly admitted that the militarization of the United States rendered the assistance of a British garrison meaningless for the defence of the North American colonies. Based on the impracticality of maintaining a garrison for a futile defence, the Province of Canada became increasingly responsible for its own security.

As British military commitments waned and Canadian defence policy was being negotiated, the Fenian Brotherhood emerged as an intimidating threat to British North America. Reports of imminent Fenian invasions in 1865 and 1866 led the Canadian and British forces to prepare for the seemingly inevitable clash. The shrinking British garrison was temporarily reinforced, and Canadian militia units were placed on high alert. The Fenian threat also brought the Canadian militia into the focus of policymakers because military reforms since the Act of Union remained untested.

During the early 1840s, the Canadian militia was based on the sedentary militia, which filled its ranks through a policy of compulsory universal service. It claimed 426 battalions and 235,000 troops. Although seemingly impressive, the vast majority were untrained and unequipped for combat. Gradually, the Canadian militia shifted from being centred on compulsory service to voluntary service. In 1846, provisions were made to authorize a voluntary force of 30,000 strong but voluntary units needed to finance their own expenses. Another major change was made under the Militia Act of 1855. In accordance with the act, the government effectively abandoned compulsory service and pledged to fund an “Active Militia” of 5,000 volunteers to form companies of infantry, cavalry and field batteries.

The stability of the voluntary system had mixed results as military enthusiasm ebbed and flowed. For instance, voluntary enlistment rose alongside the excitement around the Crimean War, the Indian Mutiny and the royal visit by the Prince of Wales in 1860. The latter even led to the formation of new units, such as Toronto’s Queen’s Own Rifles. As excitement faded and recessionary pressures mounted, the ranks of the voluntary units declined. Another systemic problem of the Canadian militia was its dubious combat effectiveness. Militia officers were often appointed for their political and social standing rather than martial skills, while the units often behaved more like social clubs rather than organizations preparing for life-and-death struggles. In contrast, many Fenian soldiers were battle-hardened veterans from the American Civil War and other conflicts, so there was no telling how the Canadian militia would fare in battle. Nevertheless, the Canadian militia maintained a significant advantage from the support of the British garrison and British intelligence. The heightened sense of insecurity in Canada also led to an influx of recruits, bringing Canada’s voluntary force to 35,000 by 1863.

The Battle of Ridgeway

The first major Fenian incursion into British North America was led by O’Mahony’s faction. The premise of the offensive was to occupy Campobello Island in New Brunswick so that British troops could be diverted from responding to a major uprising in Ireland. By March 1866, British intelligence had discovered the plan. Armed vessels were deployed to the island’s surrounding waters, the local militia units were mobilized, and 700 British regulars reinforced the area. A minor skirmish took place on a nearby island, but the Fenian campaign was immediately thwarted. While the episode was short-lived, it stands out for boosting the popularity of Confederation, especially in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

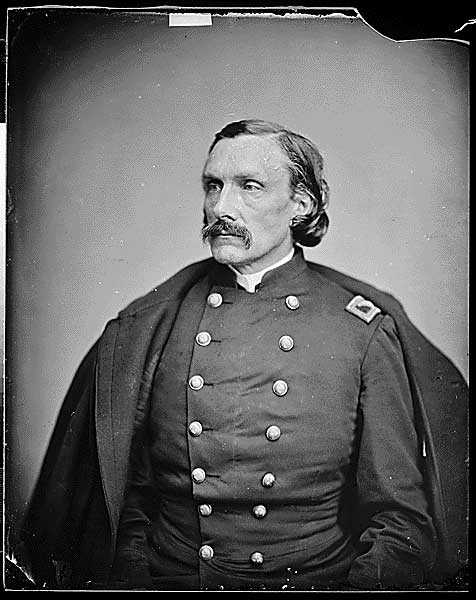

The Fenian offensive undertaken by Roberts’ faction was considerably more ambitious. Overseeing the campaign was Thomas W. Sweeny, a former regimental officer for the United States Army with 20 years of experience. The overarching objective of the campaign was to engage British and Canadian forces along the St. Lawrence River so that other Fenian units could occupy the Eastern Townships in Quebec. After the Eastern Townships were secured, the Fenians planned on establishing their headquarters and a provisional government. Importantly, the occupation on British soil would prevent the American authorities from intervening under the pretext of enforcing the Neutrality Act. This would allow the Fenian Brotherhood to focus on additional military actions, particularly sabotaging Canadian infrastructure and raiding British shipping. The occupation and attacks were planned to continue until the British government conceded to Irish independence.

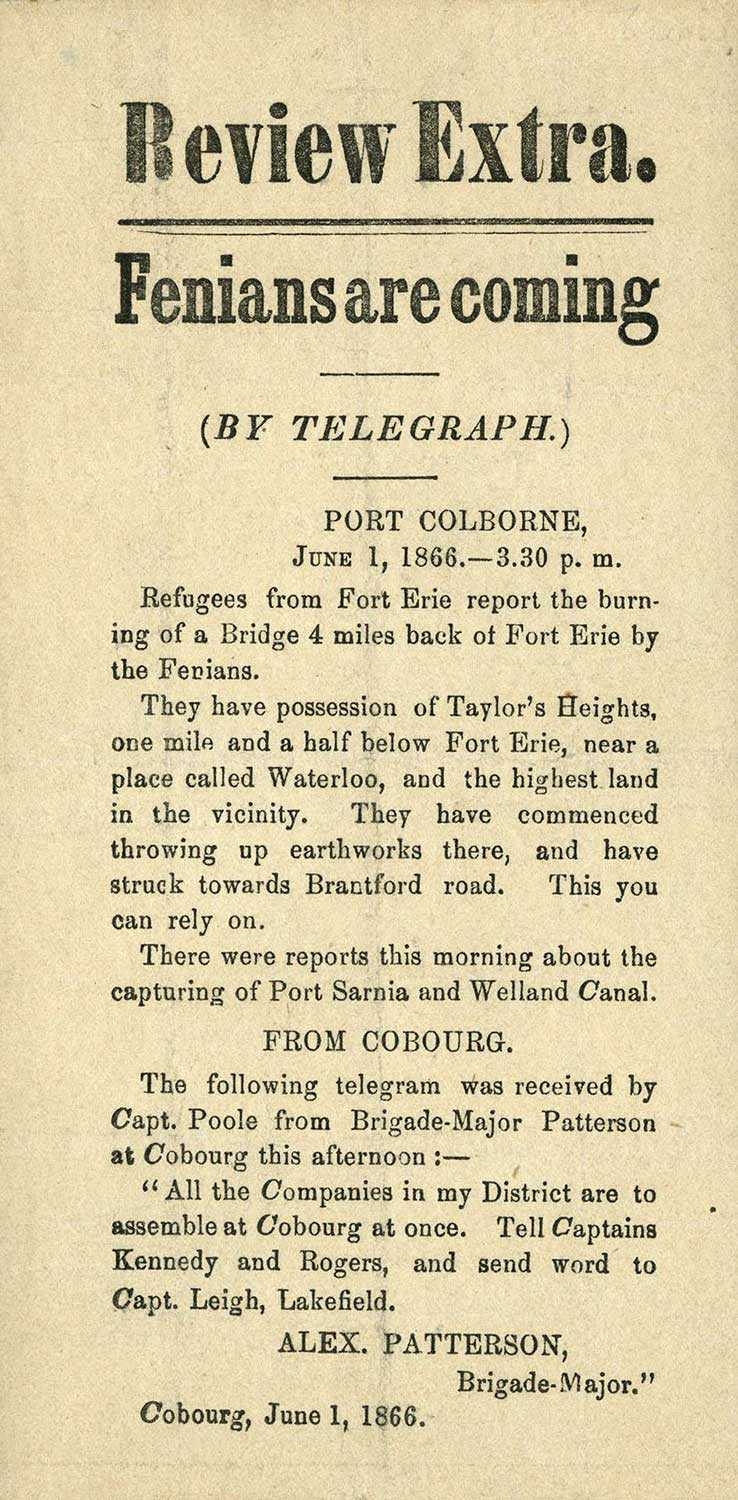

In late May 1866, Fenians began amassing in Chicago and Buffalo. The alarmed United States District Attorney, W.A. Dart, alerted the Canadian authorities in Hamilton and Toronto, and British informants verified the arrival of Fenian military supplies. The Fenian offensive from Chicago was obstructed by the unavailability of water transport, but the Fenians in Buffalo had no such problems. On June 1, between 700 and 800 armed Fenians led by John O’Neill crossed the Niagara River one mile north of Fort Erie. O’Neill’s army secured the surrounding area, including the undefended town of Fort Erie. Mounted scouts were dispatched to survey the area and inform the local inhabitants that no harm would come to them. For the rest of the day, the Fenians established fortifications, handled logistical issues, and prepared to move against the Welland Canal.

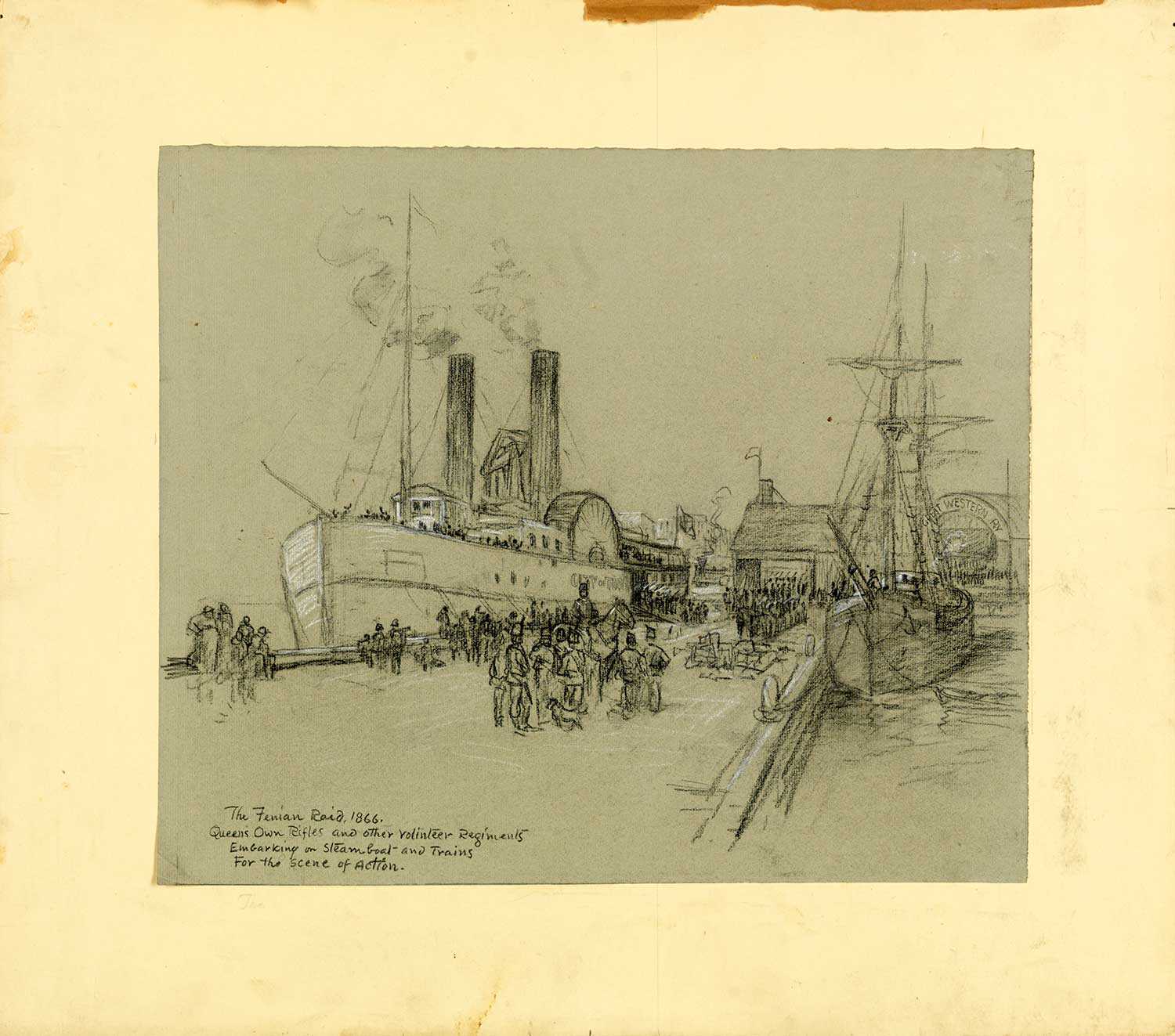

The Fenian invasion sent the Canadian military into overdrive. In Canada West, 67 militia units were mobilized on June 1. The following day, an additional 12 militia units were mobilized, and 31 new militia companies were formed. Expectedly, British regulars were also mobilized, including the British 47th Regiment of Foot. Commanding the British troops in Canada West was Major General George Napier, who promptly dispatched reinforcements to the Niagara Peninsula.

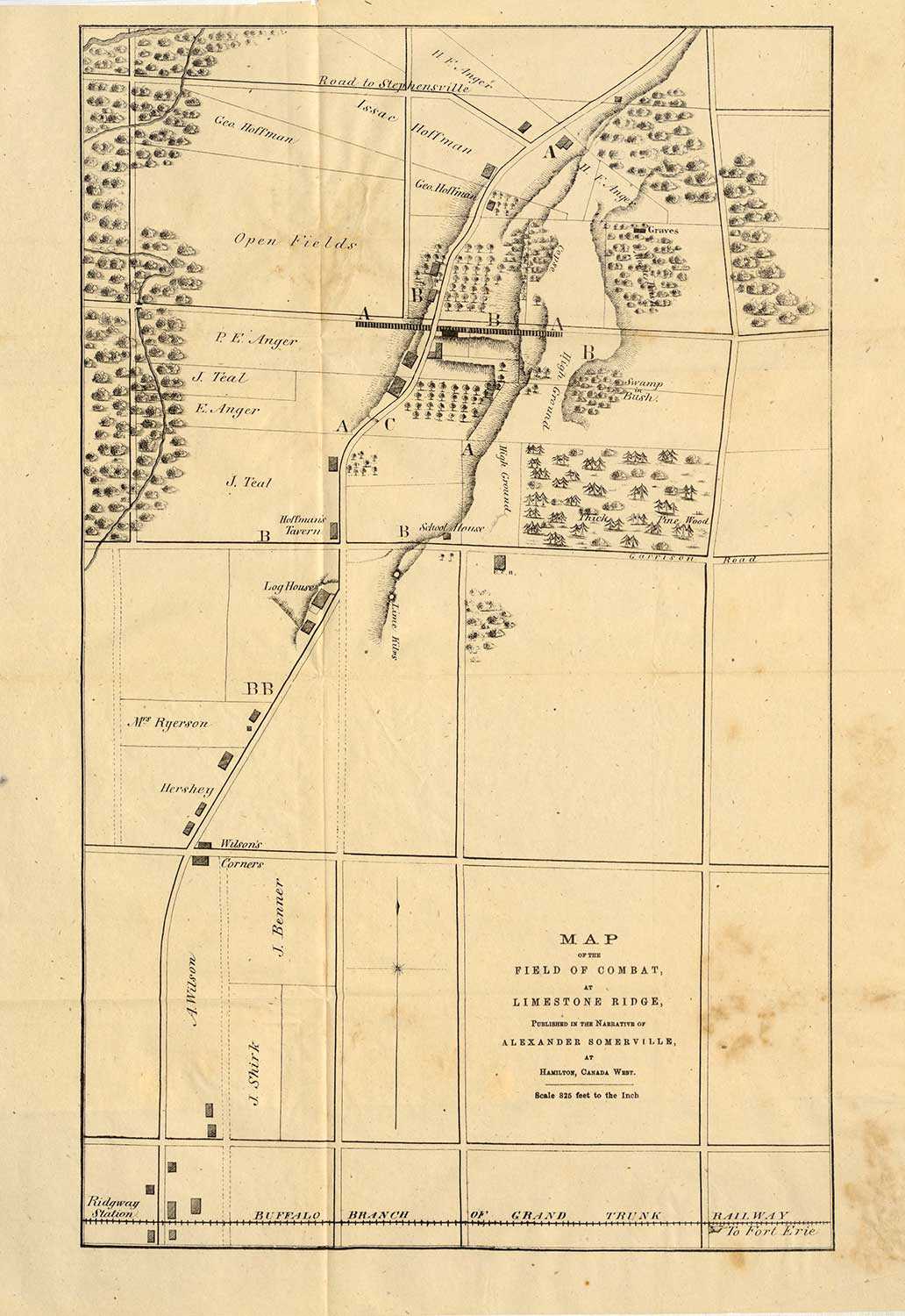

On June 2, O’Neill marched his army to Lime Ridge Road, which connected to the village of Ridgeway. As alluded to by the road’s name, the natural feature of the area was a ridge nine to 12 metres (30 to 40 feet) high and 0.8 kilometres (half a mile) wide. Notably, there were also forests over 900 metres (1,000 yards) from each side of the road. O’Neill’s scouts reported enemy troops closing in on their position, so O’Neill ordered the Fenians to set up barricades and posted pickets in the forests. In the early morning, a unit from the 10th Highland Company of Toronto, which at the time was part of the Queen’s Own Rifles, spotted the Fenians. Lt.-Col. Alfred Booker, a militia officer with no battle experience, held senior command over the force of 840 Canadian militia. Importantly, he did not have mounted scouts to provide him with detailed information regarding the enemy positions or composition. Although the lack of information was a major disadvantage, Booker decided to engage the enemy regardless. He ordered soldiers from the Queen’s Own Rifles to skirmish the enemy pickets in the forest to flush them out. The initiative was largely successful, and Booker rotated the Queen’s Own soldiers with those from the York Rifles and the red-coated 13th Hamilton Battalion.

O’Neill decided on a counter-attack. In loose formation, Fenian soldiers made their advance towards the Canadian position, and the inexperience of the Canadian militia began to show. Booker was inaccurately alerted of an impending cavalry attack, leading him to order companies of the Queen’s Own to form a square. After realizing that there was no cavalry, Booker ordered the units to reform columns but disorder ensued. Canadian militia officers added to the confusion by issuing contradictory orders to retire, advance and halt. Meanwhile, the Fenian troops were firing upon the manoeuvring and disorganized Canadian militia. It was not long before the battle broke and the Canadian militia retreated. Rather than pursue, O’Neill withdrew to Fort Erie to await reinforcements. In the two hours of fighting, the Canadian militia suffered nine deaths and 33 casualties (four of whom later died). The Fenians are estimated to have suffered a similar number of fatalities.

While at Fort Erie, a second skirmish occurred between the Fenians and a small force of Canadian militia led by Lt.-Col. John Dennis. The engagement ended as a second victory for O’Neill. The Fenian commander, however, faced a difficult decision. O’Neill had approximately 2,000 troops in Buffalo ready to reinforce his position, but his army was already facing food shortages. Moreover, the Canadian and British troops were rapidly amassing on the Niagara Peninsula. The astute tactician knew that the odds were quickly stacking against him, so rather than make a bloody stand, O’Neill claimed “victory” and retreated to American soil. As the Fenians crossed on barges, they were intercepted by American vessels who escorted them for the rest of their journey. Eager to defuse the situation, the American government granted the rank-and-file troops free passage to return home, but on the condition that they accepted parole. O’Neill was arrested for violating neutrality laws, but the charges were dropped.

Watch this video of the Fenian Raids, as told by The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada Regimental Museum. The Queen’s Own Rifles is the oldest, continually serving infantry regiment in Canada.

The aftermath of Ridgeway

The Battle of Ridgeway became a major boon to the Fenian Brotherhood. O’Neill became a hero within the movement and gained enough supporters to lead his own faction. But while he achieved success in 1866, O’Neill’s future endeavours were doomed to failure – if not from the progressive splintering of the Fenian movement, then because one of his most trusted advisors, Henri Le Caron, was actually a British spy. The Fenians continued their campaigning and launched a series of unsuccessful attacks. The most significant confrontation was in Quebec during the Battle of Eccles Hill in 1870, which ended in defeat for the Fenians at the hands of the Canadian militia and the Home Guard. In addition to incursions, the Fenians also attempted to meddle in Canadian affairs. In 1868, Thomas D’Arcy McGee was assassinated. O’Neill also unsuccessfully tried to recruit Louis Riel and the Métis into an armed coalition. In the fall of 1871, O’Neill and a small group of followers were apprehended during a raid on a Hudson’s Bay post. This failed incursion marked the end of the Fenian raids.

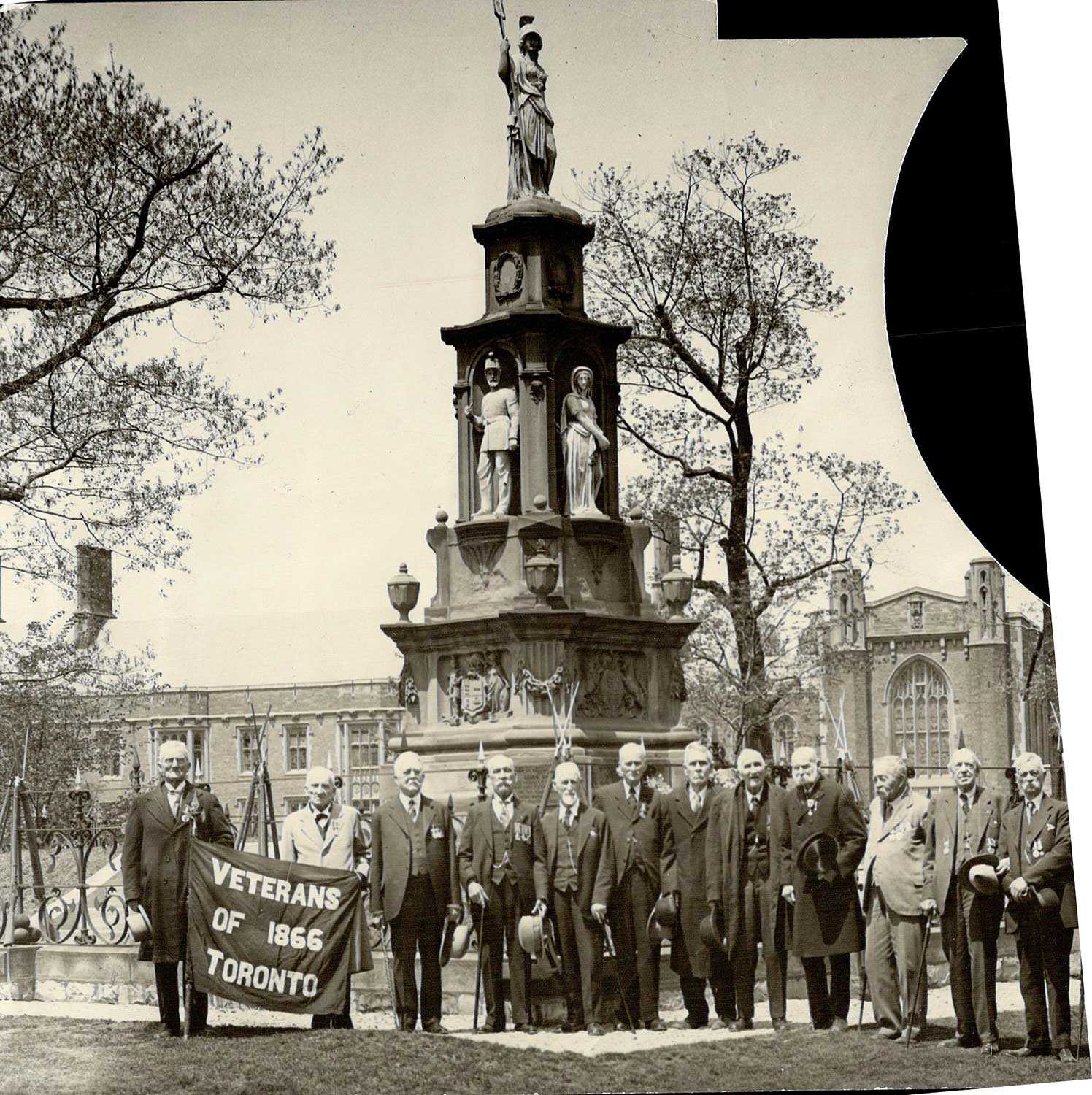

The threat posed by the Fenian Brotherhood was almost always exaggerated, and yet it had a meaningful impact. As the British government cut back on their military commitments in Canada, the Fenian threat led to widespread support for the development of a Canadian militia and allowed the Canadian militia to test changes to its organization. The Fenian threat also occurred during a period when Canada’s political leaders were negotiating Confederation. The backdrop of an external military threat proved valuable in these political discussions. It gave credibility to the arguments in favour of political consolidation and the investment in infrastructure to link the colonies. For Ontario, the defeat of the Fenian Brotherhood imbued the province’s militia units with pride that has become part of their regimental histories. Although the Fenian incursions marked the last invasion in Ontario, the province’s military would continue to fight for Canadian and British interests in the years to come, even beyond the territorial boundaries of the province.

Lastly, the Fenian Raids were significant in the lives of Ontario’s inhabitants. The raids connected to a long-standing cultural memory of threats originating from across the American border, including attacks during the War of 1812 and the Rebellion of 1837-38. Later, in the First World War, this cultural memory re-emerged alongside rumours that tens of thousands of German-Americans acquired rifles and were planning a major invasion. There was even a false alarm of an impending German zeppelin attack launched from American soil. The threat was taken seriously enough that the lights in Ottawa’s Parliament buildings were turned off, and snipers were posted on the roof. Such an attack seems somewhat preposterous in historical retrospect. For those who lived through the turbulent period of the early to mid-19th century, as well as their direct descendants, the possibility would not have seemed so far-fetched.