Menu

Military operations and experiences

Introduction

By the summer of 1940, Nazi Germany had conquered most of continental Europe, and the United Kingdom was defending itself against the German Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain. During these trying times, Canada became the United Kingdom’s most important ally. To make a meaningful difference in the war, Canada’s military would require expansion and modernization. To this end, the Canadian government authorized massive military expenditures. Between 1937 and 1939, the military’s annual budget was $36-37 million. Between 1939 and 1950, military expenditures increased to over $21.7 billion. This section explores Ontario’s contributions to the three military services during this period of expansion and modernization. It also considers how military recruitment policies regarding women and visible minorities changed during the war.

Royal Canadian Air Force

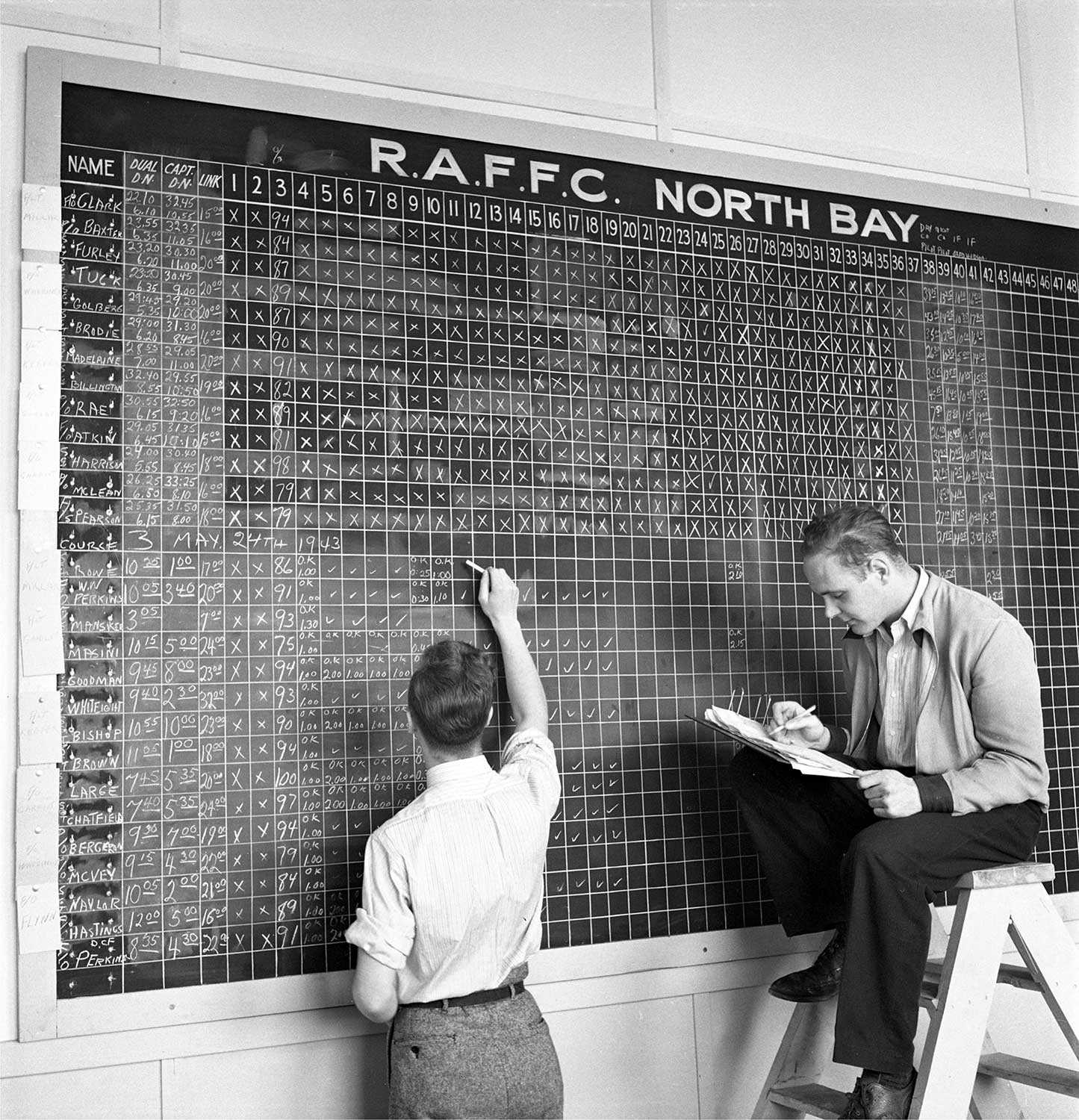

At the outset of hostilities, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) focused on co-ordinating operations with the navy to secure Canada’s Atlantic seaboard and protect transatlantic convoys. The No. 1 (RCAF) Squadron, composed of 16 Hurricane aircraft, was also despatched to England in time to fight in the Battle of Britain. Although these were meaningful contributions, the RCAF’s most important contribution during the first half of the war was the establishment and administration of The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP). To this day, the BCATP remains one of the most extensive aviation training programs in all of history. It produced 72,835 aircrew for the RCAF and 58,718 aircrew for other British Commonwealth air forces. Canada also trained Allied nationals from France, Belgium, The Netherlands, Czechoslovakia, Norway, Greece, Poland, Yugoslavia and China.

Ontario was an ideal location for air training because of its stable weather conditions, security from the Axis powers and large population. The BCATP also benefited from the growth of Ontario’s aviation industry, which supplied an increasing number of aircraft. That said, establishing the BCATP was no minor undertaking and cost $1.76 billion. Although the program benefited from a large influx of money, its expansion proceeded gradually because of shortages of both aircraft and instructors. For instance, nearly all the graduates who completed their training in November 1940 would serve as instructors rather than serve overseas as pilots. British and American instructors were hired to help offset this shortage.

By 1941, the air training program had transformed from a few scattered schools into a complex educational infrastructure. At the centre of the program was Trenton’s Central Flying School. It was responsible for centralizing and standardizing flying instruction. For elementary flight training in Ontario, trainees would attend one of the schools in Malton, Thunder Bay, London, Windsor, Mount Hope, Pendleton, Goderich, St. Eugene or Oshawa. On completion, trainees would progress to a Service Flying school at Camp Borden, Ottawa, Brantford, Dunnville, Centralia, Aylmer, Hagersville or Kingston. Only one-tenth of operational training was completed in Canada, but schools in Ontario offered many specialized courses, including technical training, wireless operations, bombing and gunnery, flight engineering, air navigation, air observation and instrument flying.

The RCAF stands out for its popularity. Indeed, the high number of applicants enabled the RCAF to create a reserve pool that enabled the service to avoid enlistment shortages. A total of 90,518 Ontario men enlisted in the RCAF, representing 40 per cent of the RCAF’s wartime enlistment.

Women were also eager to enlist. Initially, women could only serve in the RCAF as nurses. In July 1941, however, the government lifted the ban and established the RCAF Women’s Division. As implied by the recruitment slogan – “We Serve so That Men May Fly” – the objective of the Women’s Division was to replace men in non-combat roles so that men could fight directly. The RCAF maintained a rigid division between men and women, but gradually some divisions were removed in select areas. For instance, in 1943, the RCAF lifted gender segregation in training programs. Furthermore, women’s wages continued to rise until they reached roughly 80 per cent of male wages, and eventually had access to 65 out of 102 possible trades. Despite these barriers, over 17,000 women joined the RCAF. Nearly one-third were Ontario residents.

Hundreds of Canadian aircrews served in Royal Air Force (RAF) squadrons as well, but in April 1941, the RCAF established itself as a separate operational group. It was a welcome development for much of the Canadian public who clamoured for distinct Canadian units overseas. Within a few years, the RCAF’s operations were far-reaching. In December 1944, the RCAF had deployed 46 squadrons – a far cry from the single squadron that could be spared at the start of the war. They served in the No. 6 Bomber Group (equipped with the new Lancasters in 1944), Northwest Europe, Italy and Burma (where the RCAF challenged Japanese air superiority). Among the most famous RCAF pilots was “Buzz” Beurling, who was credited with shooting down 29 German aircraft during the Siege of Malta. Overall, the RCAF’s operations during the war came at a high price as a staggering 17,191 aircrew perished.

The Canadian militia/army

At the beginning of the war, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King believed that Canada’s contributions to the Allied war effort would be focused on industrial production and assistance from the air force and navy. The stunning defeat of France in June 1940 meant that this plan would now have to be altered because it resulted in the loss of the largest Allied land force. Consequently, Canada was pressured to help fill the void.

At the end of 1938, Canada’s Regular Army (known as the Permanent Active Militia until 1940) only numbered 4,169. The Reserve Force was much larger and had 51,418 personnel, which included all army services such as staff, artillery, infantry, engineering, signals and others. Not surprisingly, the shortcomings of this small force would have to be addressed. To fund the army’s expansion and modernization, the army’s budget increased by over 400 per cent between 1940 and 1941. It reached a high point of $1.34 billion between 1943 and 1944.

Expanding the army’s budget was relatively straightforward, but the methods of recruitment was a sensitive political issue. Many politicians still remembered the civil unrest caused by the conscription crisis during the First World War. These experiences inspired a more cautious approach this time around. Under the National Resources Mobilization Act (NRMA), authorized on June 21, 1940, the military could conscript individuals to serve on the home front. As the war effort intensified, however, King came under pressure to use the conscripts for service overseas. Not wanting to betray public confidence, King issued a plebiscite on April 27, 1942 to legitimize the new terms of conscription. Ontario demonstrated considerable support with a vote of 82.3 per cent in favour, but it remained a divisive issue on the national level. It was not until the summer of 1944, after casualties from D-Day, that King’s government passed an order-in-council authorizing conscripts to serve overseas. The order was later legitimized by a vote in Parliament of 143 to 70.

For First Nations, conscription was a violation of their sovereignty and a disregard of their cultural traditions that allowed individuals to choose whether they would go to war. This tradition worked in favour of the British during the War of 1812, as some First Nations warriors defied consensus in their communities by joining British forces. But adding to the frustration of First Nations was how the Canadian government continually disregarded their social and legal interests, leading them to challenge the premise of their civil obligations. In some areas, opposition to conscription escalated. In one tragic instance, three Mohawk men were shot during the resistance to conscription on the Caughnawaga Reserve. In response to spontaneous and organized opposition, the government ceased their attempts to conscript Indigenous men in the final months of the war.

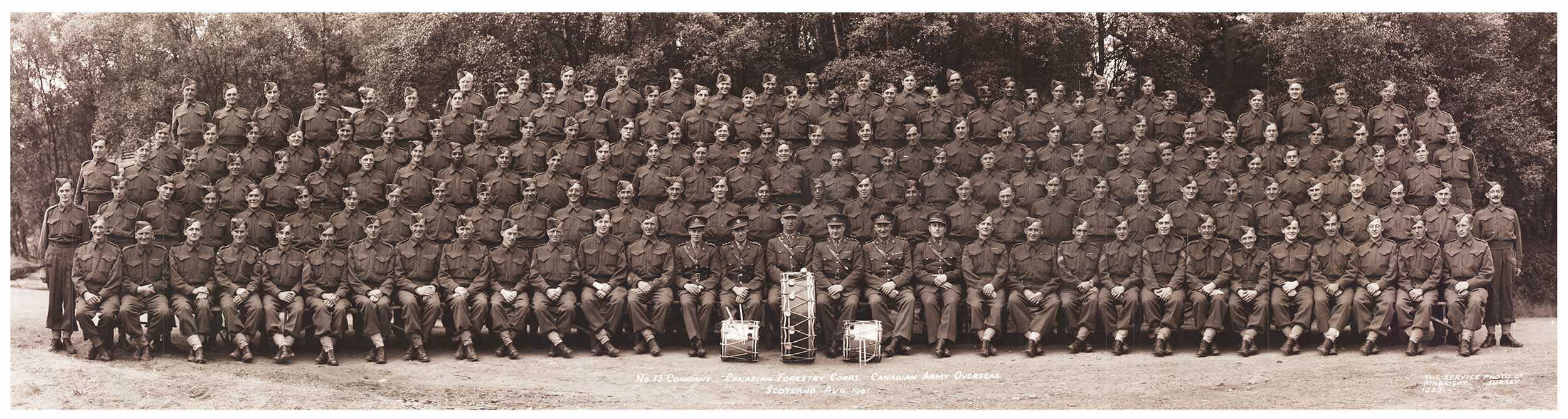

By 1945, Ontario provided 23,822 out of the total of 100,573 NRMA conscripts. Almost 13,000 conscripts would be sent overseas; 2,463 served on the battlefield and 69 were killed. In addition to conscripts, the Regular Army recruited 608,434 soldiers throughout the war. Forty per cent of them were permanent residents of Ontario. To accommodate this massive influx of soldiers, training centres were opened across the province. Officers trained at the Royal Military College in Kingston and the Officer Training Centre in Brockville. Basic training was held at one of 12 training centres. Engineering and artillery training were taught at Petawawa, while Camp Borden was used for armour corps and infantry corps training.

As evident during the First World War, many women were also eager to perform wartime duties to enable more men to serve in combat roles. Unlike the United Kingdom, which allowed women to serve in the army since 1938, the Canadian government restricted women’s roles to nursing. In defiance of these regulations, Ontario women formed paramilitary organizations to train themselves. For example, the Women’s Volunteer Reserve Corps offered training in motor mechanics, driving, small arms handling, code signalling, quartermaster duties, map reading, first aid and administration. Since the government did not provide subsidies, participants had to cover the organization’s expenses. When Canada’s war effort intensified in 1941, the government reversed course and formed the Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC) on August 13. Eight months later, the CWAC was re-organized as an official part of the Regular Army. The Ontario Agricultural College administered basic and advanced training programs for women in Kitchener. From the 21,618 CWAC members who served, 7,508 were from Ontario. Almost 2,000 CWAC members served overseas.

By early 1944, the army had 495,804 personnel from all ranks, including NRMA conscripts and CWAC members. Nearly half of this force was serving in the European theatre. At this juncture, the Canadian army had suffered some defeats but had also achieved some success. In Hong Kong, two battalions, which were under-trained and ill-equipped, were defeated by the Japanese. Between the attack and the harsh conditions of Japanese internment, 500 Canadian soldiers were killed. The Dieppe Raid on August 19, 1942 was another defeat. The Canadian forces launched an amphibious landing against German beachhead defences. Out of nearly 5,000 soldiers, 907 were killed and 1,946 taken prisoner. Although the Dieppe Raid failed, it provided important lessons to guide preparation for the invasion of Normandy.

The Canadian army found more success during the invasions of Sicily and Italy. The 1st Canadian Infantry Division and the 1st Canadian Tank Brigade fought fierce battles against Italian and German forces, including assaults against the heavily fortified Gustav Line and Hitler Line. Fighting was brutal and the casualties amounted to 26,254.

Among the army’s greatest victories was the invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944 – D-Day. Canadian ships, planes and soldiers launched a major assault on Juno Beach while Canadian paratroopers landed behind enemy lines. The defences at Juno were the most difficult among those assigned to the British Commonwealth forces, but the 3rd Canadian Infantry and the 2nd Armoured Brigade succeeded at the cost of 1,074 casualties. After D-Day, the Canadian army fought major engagements at Caen, Falaise and Scheldt in Northwest Europe, as well as the Gothic Line in Italy.

The Royal Canadian Navy

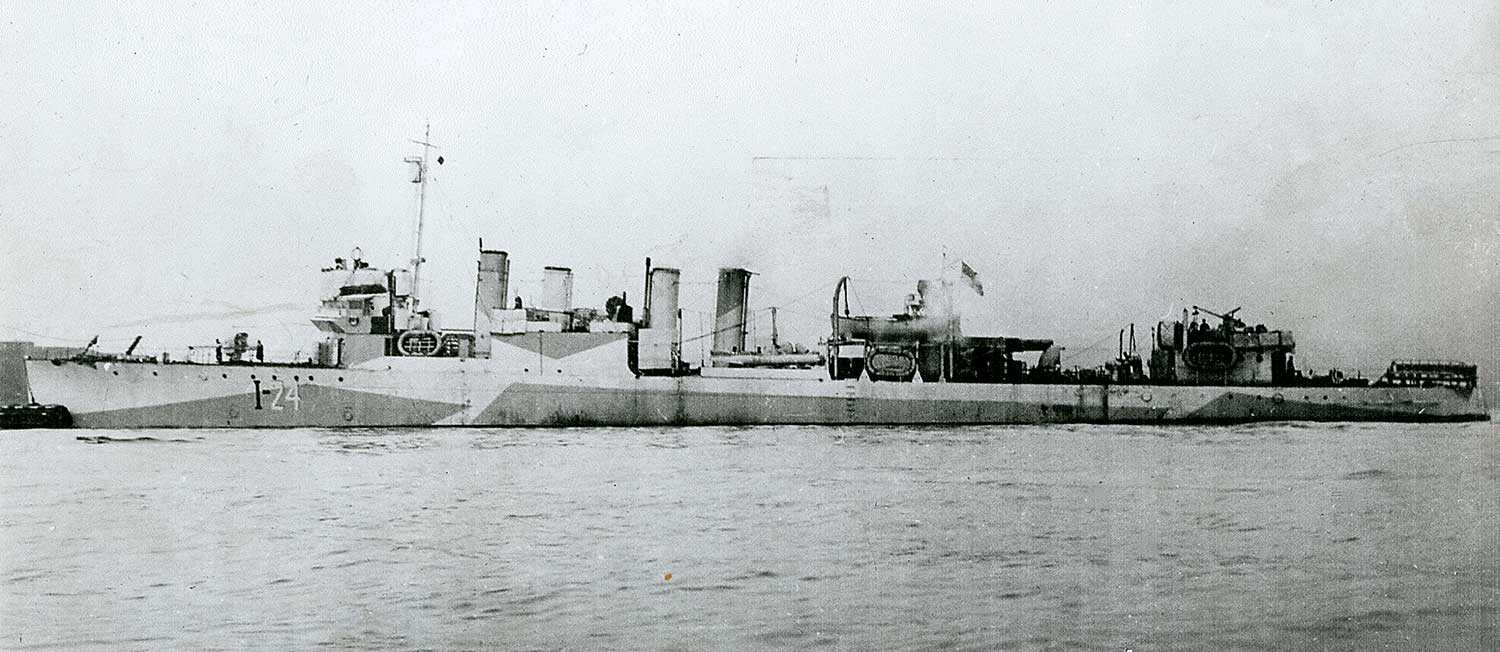

During the interwar period, the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) remained a relatively minor force. It had expanded modestly by purchasing four destroyers from the British Admiralty, bringing the RCN’s total number of destroyers to six. The RCN also added four Canadian-built minesweepers. In terms of personnel, the RCN had only 309 officers and 2,967 ratings (generally enlisted occupations) by 1939. At the beginning of the war, the RCN answered the request by the British government to send reinforcements. As Canada sent four destroyers to the British Isles, the directive of the RCN was clear. Their priority would be to expand the number of military and merchant vessels to protect and bolster transatlantic convoys.

As a means of immediate expansion, the RCN purchased seven outdated destroyers from the United States Navy. The bulk of the RCN’s expansion, however, would occur through construction. Ontario was home to numerous shipyards and contributed substantially to this part of the war effort. (See Industry and research.) Ontario also made important contributions to the RCN through enlistment. According to military records, 40 per cent of the members of the RCN in 1945 were permanent residents of Ontario, a total contribution of 40,353 personnel. This number was particularly impressive for a province that had no direct ocean access. It was also a necessity for filling the ranks of the RCN’s expanding fleet, which increased from 13 vessels to 939 by the war’s end. Many ships were named after Ontario towns and cities to honour the province’s contributions. One cruiser was even christened the HMCS Ontario.

Before 1939, RCN cadets were required to train in England because the Royal Canadian Naval College closed in 1922. The increased demand for naval personnel, however, necessitated naval training closer to home. Several Ontario colleges and universities provided training courses, including Western, McMaster, the University of Toronto, the University of Ottawa, Queen’s, St. Patrick’s College and the Ontario Agricultural College. The rising number of personnel also incentivized the RCN to establish its own naval hospitals in 1941. Nursing Sisters were increasingly trained within the special medical system established by the RCN and, furthermore, the RCN changed the rank of Nursing Sister to Nursing Officer. By 1945, there were 345 Nursing Officers. The integration of female nurses, however, did not reflect exceptionally progressive leanings. The RCN was the last military branch to authorize women for service – a change that occurred on July 31, 1942. The first class taught for the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service (WRCNS) was held at Galt (now Cambridge). After training, naval servicewomen (nicknamed the “Wrens”) were employed in various trades, ranging from administrative positions to transport operations and telecommunications operators. The Wrens would have a peak strength of over 6,700 before disbanding in 1946.

The greatest threat to the RCN was German submarines or U-boats, which harassed ships as close to Canada as the coast of Newfoundland and the Gulf of the St. Lawrence River. In 1942, 14 ships were torpedoed in Canadian waters, including two corvettes. As the RCN ships became more numerous, organized and equipped by the autumn of 1943, the U-boat threat diminished. Eleven RCAF squadrons patrolled the Atlantic alongside hundreds of RCN ships. The RCN also participated in combined operations, such as the invasion of Sicily, Italy and Normandy. In total, 31 RCN ships were sunk, and 2,024 lives were lost.

Racial barriers to enlistment

Indigenous, Black and Asian communities in Canada demonstrated their support for the war effort through donations of money and materials, organizing patriotic processions, and observing wartime regulations. Six Nations on the Grand River went even further by donating land for military use. Of course, enlistment was among the most honourable acts, but the opportunity to enlist was limited by racial barriers.

Out of the three military services, the army had the least racially restrictive policies on enlistment. Official policy dictated that officers were required to be British subjects, but even this requirement was removed shortly after September 1939. Discrimination, however, persisted informally. The commanding officer of a military district had the discretion to accept or refuse candidates. There were occasions, however, when Army Headquarters intervened. For instance, military districts were instructed not to form race-based units, such as the all-Black unit formed during the First World War. Ministers also discouraged the enlistment of Black immigrants from the British West Indies. Despite these attempts at dissuasion, military districts still accepted dozens of applicants. It is difficult to quantify the enlistment of visible minorities because the military did not keep records based on racial identity. The exception to this was the Department of Indian Affairs, which recorded 3,090 Indigenous enlistees, including 16 women. Ontario’s contribution to this total was 1,324. Most of the recruits were from the Six Nations at Manitoulin Island, Parry Sound and Tyendinaga. The McLeod family from the Cape Croker Reserve on the Bruce Peninsula made an exceptional contribution: six sons and one daughter. Tragically, two sons were killed in action and another two were wounded. To honour their family’s sacrifice, Mary Louise McLeod became the Silver Cross Mother in 1972.

In contrast to the army, the RCN and RCAF maintained their formal policies of racial discrimination in recruitment for a longer period of time. In 1938, the navy and air force detached from the militia administration and became their own independent military services. Building on the policies of their counterparts in the British military, both services instituted guidelines requiring enlistees to be white and British subjects. There were some exceptions to this rule, but ultimately the RCN and RCAF opposed the enlistment of visible minorities. In January 1941, the RCAF removed racial restrictions for general duty tasks, such as clerks and cooks, but applicants had to be approved by the RCAF Headquarters. The RCAF finally revoked its racial requirements in February 1942, while the RCN only removed restrictions in July 1944. Although formal policy had changed, applicants could still be turned away by recruitment officials.

While experiences in the military were shaped by racial prejudice and discrimination, historians have noted through oral testimonies that many servicemen and servicewomen remembered how a spirit of camaraderie often transcended gender, ethnic and racial divisions. This was not always the case, as some individuals and units could exhibit pronounced discriminatory behaviour. And yet, the resolve of non-white military personnel to serve played no small part in challenging the prevalence of discriminatory behaviour during and after the war.