Menu

Anti-alien hostility

Introduction

At the beginning of the Great War, Canada had many residents who would be described as having “enemy origins.” According to the 1911 census, over half a million residents could trace their origins to Germany or Austria-Hungary. These residents accounted for 7.25 per cent of Canada’s total population. Ontario was home to nearly half of Canada’s residents of German origin, or, more specifically, 192,320 people. In contrast, there were 11,771 residents of Austro-Hungarian origin, many of whom were Ukrainians. Importantly, less than 8 per cent of Germans in Canada were born in Germany, which amounted to only 15,010 people. This meant that there would be few Germans in Canada that had an obligation to serve as German reservists. On the other hand, most Austro-Hungarian residents had immigrated to Canada since 1901, so they were more likely to be Austro-Hungarian nationals with obligations to serve Canada’s enemy. But in addition to the threat of reservists, British Canadians in Ontario became increasingly hostile towards German and Austro-Hungarian residents and suspected that they were disloyal to Canada.

During the war, the term “enemy aliens” was used to draw attention to the threat posed by these non-naturalized residents of so-called enemy origin. Often the use of this designation ignored ethnic particularities, such as how Ukrainian immigrants refuted association with the Austro-Hungarian empire. The sections below explore this complex history, which highlights how war-fuelled prejudice, fear and hysteria led to violence and institutional repression against ethnic minorities.

Internment in Ontario

On August 7, 1914, the federal Cabinet issued an order-in-council to arrest German reservists attempting to leave Canada. Other wartime measures followed, including the arrest of so-called enemy aliens suspected of espionage, hostile acts or any law violations. These wartime regulations were the beginning of an expansive system of restriction, regulation and subjugation. On October 28, 1914, the cabinet authorized the mandatory registration of enemy aliens. They also provided the legal groundwork for the internment of those accused or convicted of being enemy soldiers, spies and saboteurs. The Minister of Justice, Charles Doherty, however, also believed that internment could be used to “protect” enemy aliens. According to Doherty, internment was a vehicle to provide food and shelter for destitute foreigners struggling amid the recession. From this perspective, the scope of internment was broadened to include those who were non-dangerous. But while Doherty professed benevolent intentions, he was infringing on freedoms, forcing strenuous work for low pay, and legitimizing xenophobia and racism.

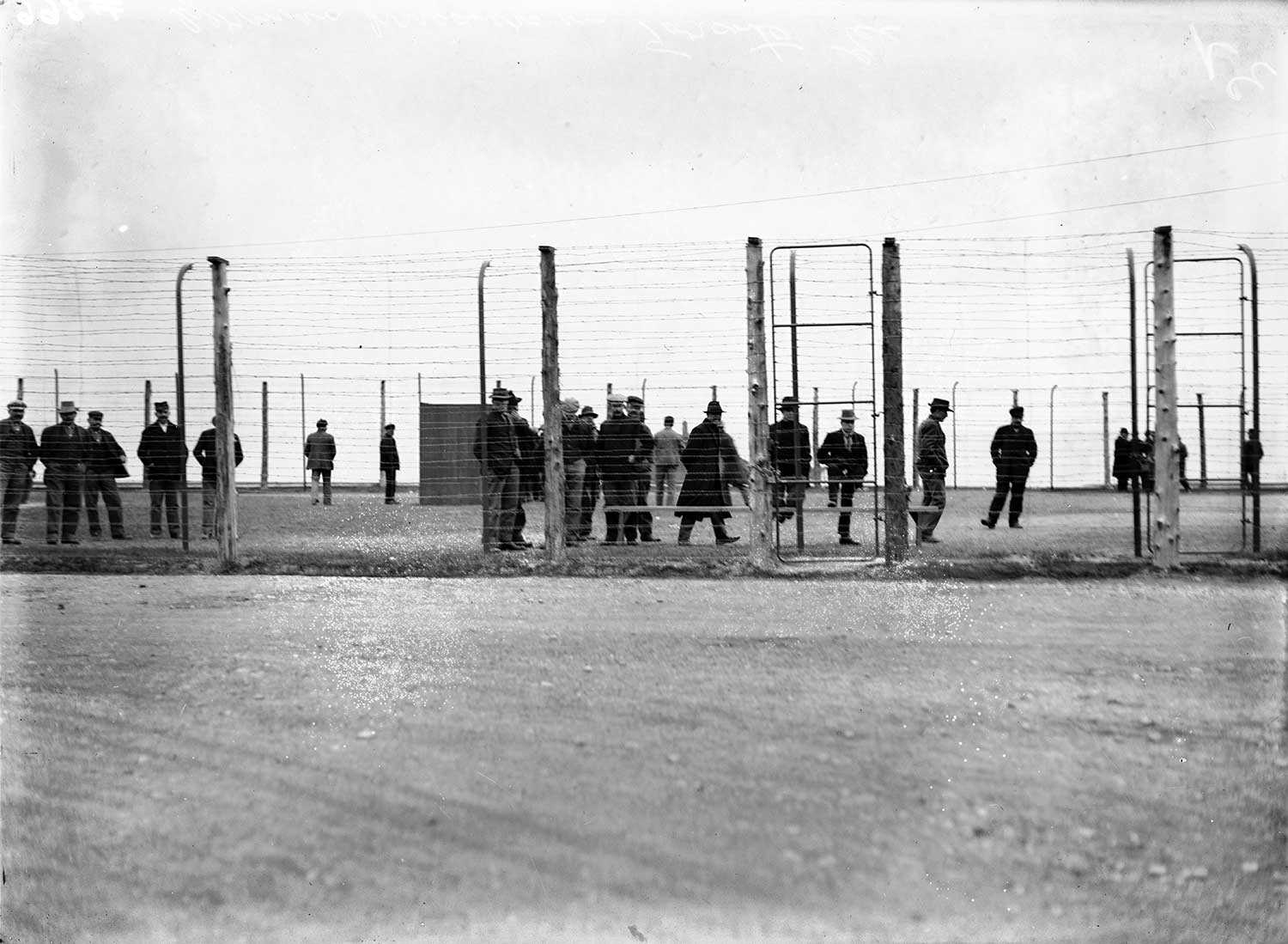

During the early months of the war, the principal facilities stationing internees in Ontario were Fort Henry in Kingston, the Stanley Barracks at Toronto’s Canadian Exhibition grounds and various prisons in forts and police stations. By the end of 1914, these facilities were overcrowded, necessitating the creation of large-scale internment camps. Ontario would ultimately have 26 internment facilities throughout the war. The first major internment camp was constructed at the Petawawa military base. A second major internment camp was created at Kapuskasing River and used for an ambitious plan to develop Ontario agriculture.

Federal and provincial policymakers decided that the internees would be used as labourers to establish an experimental farm near the transcontinental railway line in Northern Ontario at the Kapuskasing River. The project necessitated clearing the land of trees and building roads and bridges, among other strenuous work. By mid-1916, Kapuskasing Camp had over 100 buildings, 1,200 prisoners and almost 400 guards and staff.

Life as an internee in the Kapuskasing Camp was difficult and provoked resentment towards camp conditions. In May 1916, these tensions sparked a protest, which in turn escalated into a riot. The military guards responded with force and violently repressed the uprising. This response did not deter some internees from continuing their resistance by sabotaging machinery and delaying progress. In November 1917, tensions escalated into another riot. Again, guards responded with force and fired on the prisoners, hitting one. General Otter, the Director of Internment, was satisfied with the outcome.

A significant turning point in Ontario’s internment operations happened in early summer 1916. Labour Minister Thomas Crothers assembled a council to discuss potential solutions to the labour shortage. Among those sitting in the meeting were other cabinet ministers, General Otter and representatives for farming, banking and the railroad industry. Following the meeting, the government began systematically discharging internees who were deemed to be non-dangerous. As a form of parole, internees entered a private contract with a business, such as a railroad company, farm, steel mill or other business. For example, the Canadian Pacific Railway was eager to obtain prisoners to work as track labourers on the north shore of Lake Superior. While the company offered high wages, some prisoners declined these jobs because they were too physically weak after years of hard labour. For those who refused to enter these brokered contracts, internment administrators would eventually force them to leave. With large numbers of internees being released, both voluntarily and coercively, the internment facilities at Petawawa were shuttered on May 8. Kapuskasing Camp remained the major internment centre in Ontario. When the armistice was signed, there were still over 2,000 internees across the Dominion. Almost half were detained in Kapuskasing. The Kapuskasing Internment Camp officially closed on February 24, 1920 after the last prisoners were either released or deported to Europe.

Berlin (Kitchener), Ontario

Relations between British-Canadian and German-Canadian residents could be turbulent and unpredictable at best, explosive and violent at worst. Fuelling these tensions was wartime hysteria, which ebbed and flowed with wartime events. For example, reports of atrocities by the German military could galvanize mobs into a feverish rage eager to destroy German establishments. The riots in Toronto following the German attack on the passenger ship, the RMS Lusitania, is a good example.

Incidents on the home front were also provocative. In late 1914, a German conspirator with connections to the German Embassy in the United States was found attempting to blow up the Welland Canal. Other attempts of sabotage occurred in the Windsor region, targeting production facilities. Such reports led to intense paranoia. The mayor of Pembroke, L.J. Morris, went as far as to speculate that the German residents in his town were operating a massive clandestine network. But, while the presence of Germans in Northern Ontario provoked anxieties and insecurities, the city of Berlin, Ontario, became the focal point for much of the anti-German feelings throughout the province.

The social divide in Berlin was conducive to intense wartime confrontations. Out of its registered population, between half to three-quarters had German origins. The remaining population was mainly of British origin. With a large concentration of German residents, Berlin became a bastion of German culture in the face of an increasingly hostile political climate. There was no Registrar for Alien Enemies in Berlin or the surrounding Waterloo County until March 1916. Berlin even continued to circulate German-language newspapers after the introduction of nationwide restrictions. The city’s success at preventing anti-German regulations added to the perception of its disloyalty among Germanophobic residents.

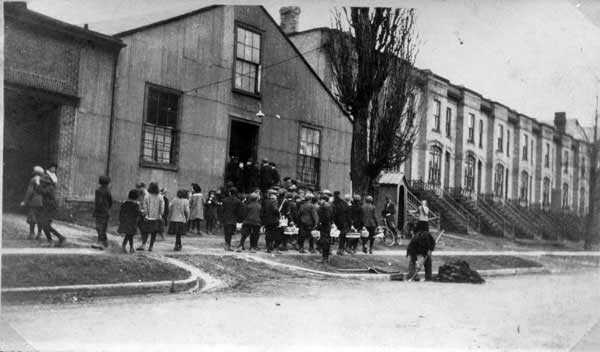

The first violent confrontation in Berlin began after the Toronto Star interviewed a local Lutheran pastor, Reverend C.R. Tappert. In the interview, Tappert defended the bitterness among Berlin’s residents towards anti-German propaganda espoused by Canadian newspapers. For Berlin’s non-German residents, Tappert’s comments were not well received. To retaliate against Tappert for his seemingly treasonous attitude, soldiers from the local 118th Battalion broke into a Lutheran clubhouse on February 13, 1916 and destroyed German flags and memorabilia. The soldiers continued to harass Tappert until a group of 60 soldiers abducted him from his home and paraded him through the streets in humiliation. Following the incident, military authorities issued warnings to the soldiers and released them on suspended sentences. Feeling vulnerable to future attacks, Tappert fled the city.

It was not long before Berlin’s pro-German attitudes provoked hostility beyond the city boundaries. Periodicals across the province relentlessly chastised Berlin for its tolerance of pro-German attitudes and lenient restrictions. In response to the growing criticism, a public meeting was held in Berlin and attendees passed a resolution to change the city’s name to something seen to be more patriotic. When residents voted on the proposal in May, it narrowly passed 1,569 to 1,488. Among the names considered for the change was Corona, but the front-runners were Brock (after the British commander Sir Isaac Brock who famously died in the War of 1812) and Kitchener (after Lord Kitchener, the former British Secretary of State for War). Ultimately, Kitchener was chosen and the city council approved the change with a vote 13 to 3.

Changing the city’s name from Berlin to Kitchener was seen as a patriotic gesture, but the friction between the city’s residents could not be so easily remedied. Indeed, the peace was broken on New Year’s Day in 1917. Preceding the confrontation, soldiers of the 118th Battalion received news that they would not travel overseas as a unit because of insufficient recruits. Undoubtedly, the soldiers felt that the broader community had failed them. Adding to the soldiers’ outrage was the announcement by the city’s mayor that he intended to restore the city’s name to Berlin. These developments, combined with the long-standing tensions between the British and German residents, made the atmosphere explosive. Later that day, there was a military parade and an onlooker attempted to take a Union Jack from a soldier. The confrontation rapidly escalated into a full-blown riot. Numerous German-owned businesses were destroyed, including the offices of the News-Record – a local English-language paper frequently criticized for its pro-German views. Rioters also assaulted city councillors. It took a detachment of 110 troops from a nearby barracks to restore order. The story of Berlin – or Kitchener – highlights how war overseas could reverberate through Ontario’s communities and bring them to the point of civil disorder.