Menu

Donning the khaki

Introduction

The soldiers who fought overseas in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) experienced a war like no other before it. The ingenuity of the modern industrial age was used to construct international war machines designed for efficient and brutal destruction. And yet, all the sophisticated machinery, tools and weaponry still required flesh and blood to operate. To win the war, Ontario’s government looked to its residents to don the khaki, but not everyone of military age was invited to do so. Informed by prevailing prejudices, military authorities prohibited enlistment based on gender and race. By the war’s end, however, the record of heroism demonstrates that bravery and excellence did not adhere to these social stereotypes. And yet, as Canada’s Great War veterans returned home and attempted to rebuild their lives, racial prejudices continued to shape soldiers’ experiences and the compensations they received from demobilization.

Barriers to serve

The war effort required the sacrifices and service of people throughout Ontario, but gender and racial prejudices shaped the expectations surrounding wartime roles. According to prevailing social norms, it was inappropriate for women to fight. Even participation in rough sports would have been considered unfeminine. Based on these views, women were told that their duty was to encourage men to enlist rather than enlist themselves. For married women, this also meant authorizing their husband’s enlistment, which remained a mandatory requirement until August 1915. Some women did manage to enlist and serve overseas but did so as Nursing Sisters in the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps. To ensure that women were fulfilling their expected roles as mothers, Nursing Sisters applicants had to be single to qualify.

Despite these barriers to serve, some women in Ontario were eager to demonstrate their usefulness beyond the roles prescribed to them. Serving in combat roles on the Western Front would have provoked insurmountable opposition, so Jessie McNab of Toronto came up with a more socially acceptable alternative. McNab organized a Women’s Home Guard to train women in first aid, nursing, shooting and military drill. The organization aimed to replace male soldiers serving on the home front so that they could fight overseas. McNab persuaded Lt.-Col. J. Galloway to oversee the training program and, within days, 400 women had signed up. When a meeting was held at McNab's home at Dundurn Heights, the overcrowded building collapsed. No one was killed, but the accident foreshadowed the fragility of the organization itself. When Galloway was elected president and McNab vice-president, McNab contested the results, stating that only women could win elected positions. In defiance, McNab refused to transfer the funds raised for the organization. With a divided leadership and no funding, the Women’s Home Guard fell into disarray, never to recover.

The Toronto Women’s Home Guard was one of many organizations that trained women to hone their martial skills for service. During the Second World War, the recruitment of women for non-combat roles in the military would be adopted more systematically through the Canadian Women’s Army Corps. Elizabeth Smellie, one of the Nursing Sisters during the First World War, would be appointed to oversee its recruitment. Collectively, these organizations demonstrate that, despite the barriers that prevented women from accessing a broader range of military roles, women were eager to serve and did so in the face of adversity.

The Canadian military also restricted opportunities to serve based on racial prejudice. At the beginning of the war, Black men in Ontario embraced the legitimacy of the Great War and sought to enlist. Only in rare cases, however, would recruitment officers accept their applications. The reason for barring Black recruits was that white military commanders tended to believe that Black men lacked the skillset to become good soldiers. There were also concerns that mixing white and Black soldiers would impact morale. Finally, some commanders believed that it was a “white man’s war,” and Black men should not have the opportunity to kill white men, even if German.

J.R.B. Whitney, the publisher of the Black-Torontonian newspaper The Canadian Observer, was confronted by this prejudice directly. In November 1915, Whitney raised 40 Black men to be part of an all-Black unit, but Minister of Militia Sam Hughes advised Whitney to abandon his efforts because no commander in the Toronto military district would accept them. It was not until July 1916, when enlistment rates were low, that the Canadian military formed a battalion for Black soldiers. Importantly, this was not a removal of racial prejudice from the military because Black men were employed as labourers in Construction Battalion No. 2, rather than given combat roles.

Despite the prevailing animosity towards Black enlistees, 350 Black men from Ontario enlisted in the Battalion. They would serve in France alongside the Canadian Forestry Corps. By the war’s end, over 1,000 Black volunteers served in the Canadian military, which put their enlistment rate on an equivalent per capita basis to European-Canadians.

Racial prejudice among military commanders and other officers also shaped the experiences of Indigenous peoples in the military. On August 8, 1914, Hughes replied to a commander who inquired about the permissibility of sending Indigenous soldiers overseas. In reply, Hughes expressed his concerns that the Germans would deny Indigenous soldiers “the privileges of civilized warfare.” Based on this view, Hughes advised military commanders to reject Indigenous enlistees for overseas service. By August 19, at least eight Indigenous men had enlisted in Ontario, because most recruitment officers denied their entry. On December 10, 1915, the Canadian Ministry of Militia and Defence changed recruitment policy and instructed recruitment officers to accept Indigenous men for overseas service. The change followed from the need to increase enlistment rates and the pressure exerted by the British War Office and Colonial Secretary Andrew Bonar Law.

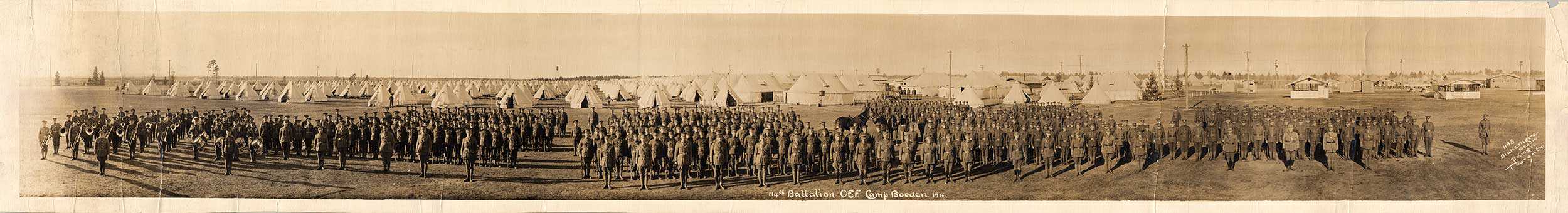

Once recruitment offices received clear instructions to recruit Indigenous men, enlistment efforts became competitive. For instance, Lt.-Col. E.S. Baxter, a respected figure among Six Nations, sought to form two all-Indigenous companies in his battalion called Brock’s Rangers. Baxter became frustrated with other battalions poaching his military district for Indigenous recruits. Meanwhile, Baxter was soliciting Indigenous soldiers to transfer into his battalion. Not all battalion commanders approved of Baxter’s plan, nor were all Indigenous soldiers eager to serve in a unit dominated by Mohawks. Still, the 114th Battalion (or Brock’s Rangers) raised 353 Indigenous soldiers, including five officers – 287 were from Six Nations reserve, and over half had previous militia experience. Ultimately, the battalion was broken up in November 1916 to reinforce other units. At least 4,000 Indigenous soldiers served in the CEF, representing 35 per cent of the registered Indigenous male population of military age.

Heroism in the theatre of war

Women and racial minority groups faced severe prejudice while serving in the CEF, but for many it did not dissuade them from performing their duty honourably.

Among the stories of perseverance and bravery was that of Edith Anderson Monture. Monture was of Mohawk descent and was born on Six Nations reserve in 1890 near Brantford. After being denied entry to nursing schools in Canada, she trained as a nurse at the New Rochelle Nursing School in New York and then enlisted with the United States Nurse Corps in 1917. She would be the only Six Nations woman to enlist in the military. Despite the obstacles in her path to serve overseas, Monture served tirelessly in a French hospital treating injured soldiers. Monture’s journey to enter military service was exceptional, prompting her to use her notoriety to advocate for Indigenous health care.

Other nurses who exhibited exceptional perseverance and bravery were Eleanor Thompson and Meta Hodge. After a German air raid bombed their field hospital, Thompson and Hodge ignored their own injuries and, instead, worked tirelessly to extinguish fires and remove injured soldiers from the wreckage. Thompson and Hodge became the first Canadian women to receive the Medal of Bravery.

Many men from visible minority groups also won recognition for their outstanding service during the war. The experiences of minority groups differed, however, including the opportunities to demonstrate bravery on the battlefield. Although there were some exceptions, Black, Asian and Indigenous men faced similar barriers to serve at the beginning of the war, however these restrictions were lifted for Indigenous men earlier than for Black and Asian men. Moreover, the prevailing stereotype of Indigenous men as “noble warriors” encouraged commanders to assign them combat roles, while some Black-Canadian soldiers who trained as infantry were forced into segregated labour units. With these dynamics in mind, the military record still shows that soldiers of all races distinguished themselves on the battlefield.

Among the distinguished Black Canadians was James Post of Ottawa. During the Battle of Passchendaele, Post took the initiative after his officers were wounded and relayed important information to his unit while under heavy fire. The courageous act won him the Distinguished Conduct Medal. Another demonstration of valour among Black Canadian soldiers was James Grant of St. Catharines who enlisted in the artillery. While fighting on the Western Front, Grant’s unit came under heavy fire and suffered numerous casualties while attempting to retrieve ammunition. Grant disregarded the dangers and made multiple trips to retrieve the ammunition. To honour his exceptional bravery, Grant became the first Black Canadian soldier to receive the Military Medal.

Among the most well-known Indigenous soldiers is Francis Pegahmagabow, an Ojibwe of the Caribou clan who was raised on what is now the Shawanaga First Nation reserve near Parry Sound. Pegahmagabow enlisted on August 14, 1914 and became a proficient sniper. By the end of the war, he claimed 378 kills, setting the world record. His exceptional skill earned him the Military Medal and two bars for bravery, thereby making him Canada’s most decorated Indigenous soldier.

Pegahmagabow was not the only Indigenous sniper who proved exceptional in the art of war. Johnson Paudash of the Hiawatha Band from Keene on Rice Lake, southeast of Peterborough, claimed 88 kills, which also earned him the Military Medal. Far from the ground but still in the battle was Oliver Milton Martin, a Mohawk from Six Nations. Martin served as a pilot in the Royal Air Force and would eventually be promoted to Brigadier General by the Second World War. He became the highest-ranking Indigenous soldier in the Canadian military.

These stories demonstrate that valour, bravery and martial prowess were not confined to gender or race.

“If ye break faith with us who die, we shall not sleep”

This line, from Lt.-Col. John McCrae’s famous poem In Flanders Fields holds meaning still today.

Listen as historian Jack Granatstein provides some history on McCrae.

For returned soldiers, re-establishment could be a harrowing experience. Physical and mental wounds were widespread following the long and brutal war. By the end of 1920, over 69,000 men and women qualified for disability pensions. The hardships of their wounds were compounded by the difficulties of finding a job during a post-war depression and of surviving the Great Influenza pandemic. Having sacrificed so much, veterans looked to the government for generous aid. Policymakers were worried, however, that large pensions and social programs would cripple the country’s post-war economy. Moreover, many policymakers believed that returned soldiers should be self-sufficient and receive assistance from private charities rather than public programs. What the government did offer was a small cash gratuity, access to vocational training programs for mechanical skills and agriculture, rehabilitation services and disability equipment, and assistance for job placements that prioritized disabled veterans.

Although some veterans succeeded in re-establishing themselves with government aid, others became destitute and endured intense hardship. The federal government’s resilience to minimize expenditures and authorize lacklustre policies prompted Lt. Dave Loughnan, Editor of The Veteran, to accuse Prime Minister Borden’s administration of “breaking faith” with soldiers. The charge was symbolic. During the 1917 federal election, the Union party used Lt.-Col. John McCrae’s famous poem In Flanders Fields to galvanize political support, but after securing 90 per cent of the soldiers’ vote and forming a majority government, it seemed to Loughnan that the Unionists abandoned their pledges to safeguard veterans’ interests. As ex-Sergeant J. Harry Fynn advocated, the government should award returned soldiers a large, graduated cash bonus based on their service. But while the so-called “Bonus Campaign” gained considerable momentum, Borden’s administration held firm against it.

Another source of frustration for veterans was the Soldier Resettlement Scheme. Using land to compensate soldiers was a tradition dating back to the settlement of New France and it continued as a form of compensation for Loyalist soldiers who fought during the American Revolution.

Ontario was the first province to offer land to Great War veterans. The first allotments were from Kapuskasing, which offered small amounts of land cleared by the internees imprisoned at the Kapuskasing Internment Camp. The scheme proved to be a disaster. Many veterans who enrolled lacked experience and capital, and while there was access to training and loans, the program was rife with insurmountable problems. The logistics of settlement, its administration and ceaseless expenses stifled its success. The environment proved inhospitable as well. Frost devastated crops and clay-ridden soil made it difficult to grow anything. Meanwhile, global agricultural prices collapsed during the post-war period, pushing even long-established and experienced farmers to the brink of poverty. By the time Ontario’s Farmer-Labour government came to power in 1919, the settled veterans were becoming rebellious. Premier Ernest Drury deemed the Kapuskasing settlement a failure and closed the program after offering the settlers financial compensation.

For Indigenous soldiers, the Soldier Resettlement Scheme had additional layers of controversy. Only one in 10 Indigenous veterans who applied to the program received loans or reserve land grants. Among those denied land, loans and grants was Indigenous war hero Pegahmagabow. For the Indigenous veterans who succeeded in receiving reserve land, land grants were awarded without the authorization of the respective band council. Moreover, the Indigenous veterans received a Certificate of Possession with dubious legal standing. These conditions put Indigenous veterans in direct conflict with their communities, dissuading some from applying. By 1927, only 184 land grants or loans were issued to Indigenous veterans in Ontario. Most of the awarded land was on reserves, while accepting land off-reserve threatened the Indigenous veterans’ legal status. Such stipulations reflected the long-term strategy of white policymakers to assimilate Indigenous peoples. As few as 10 Indigenous veterans from Ontario and Quebec succeeded in acquiring off-reserve land without losing their legal status. In further disregard for Indigenous wartime sacrifices, the Department of Indian Affairs was authorized by Order-in-Council PC 929 to expropriate land from Indigenous reserves “not under cultivation or otherwise properly used” so that white Great War veterans could be rewarded.

Demobilizing Great War soldiers was a complicated process, but for Indigenous veterans in Ontario, the process had many layers of injustice. It revealed how the war did not lead to a major shift in social prejudice nor the re-evaluation of discriminatory policies towards Indigenous people.